July 27, 2016

Your steps are light and springy as you leave the Crumlin Road Gaol. Your first day in Belfast has gone like clockwork, and now there’s only one stop left: the Peace Wall in west Belfast.

It’s a calm, balmy Friday evening as you head south towards Cupar Way. You cross Shankill Road and enter the Shankill neighborhood, a center for loyalist paramilitary action during the Troubles.

There are quite a few Ulster flags flying from houses. Many are accompanied by the Union Jack. A few houses fly the Union Jack with the flag of Ulster inset in one corner.

Other than the flags, it looks like a normal English/Irish suburb: row after row of red brick townhouses fanning off the east-west Shankill road, people rushing home from work to enjoy their weekend. There’s even a church for sale just off the main road.

Somewhere south of this neighborhood is Falls Road. Like Shankill Road, Falls Road runs east-west out of Belfast. And like Shankill, the road gives its name to the community who lives in the area. Unlike Shankill, the Falls Road community is nationalist.

Separating these two neighborhoods are no less than eight peace walls, the most famous of which is on Cupar Way.

You know exactly two things about the Cupar Way Peace Wall.

First, it’s one of dozens of peace walls built to separate Catholic (Nationalist) and Protestant (Loyalist) neighborhoods during The Troubles.

Second, the murals painted on this wall are listed as a top tourist highlight.

Your Google phone has crapped out again, which means that your Google map has gone offline.

But you know you’re close when you start to see fantastic murals on a wall across the street.

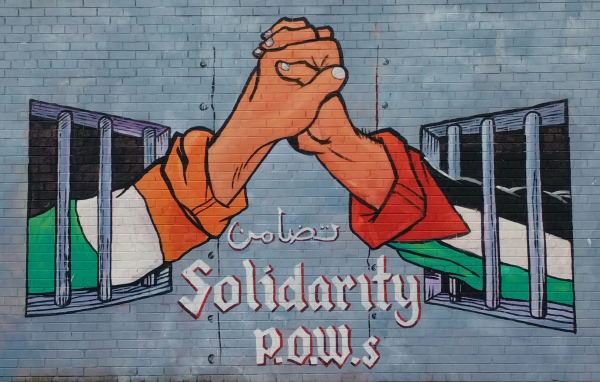

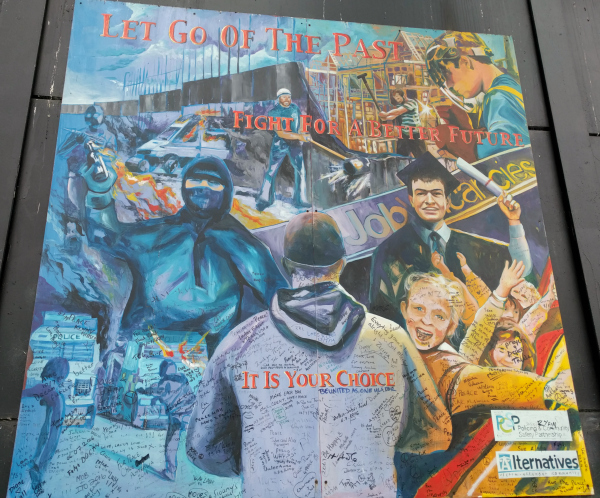

While murals like the piece about solidarity have a connection to Northern Ireland, many of the murals are surprisingly international in their social justice themes.

You’re particularly touched by this tribute to the Orlando nightclub shooting just 6 weeks earlier.

In bright, bold, beautiful murals the message of standing together to fight for these social causes is palpable.

As you round a curve in the road, the sudden presence of a Peace Gate hits you like a punch to the solar plexus.

For the first time you take in the barbed wire above the murals, and the spikes twisting and turning above the peace gates.

You’re almost afraid to walk through, as if doing so will lend credibility to this thing that should not be here.

Surely these gates aren’t still in operation?

There are no posted hours of operation. No uniformed officers. No sign that anyone is paying even the slightest attention to whether the gates are open or closed.

Yet the gates are in perfect order. No sign of rust, no sign of garbage or dead leaves collecting against the base of the gate.

You cross through the pedestrian gate, half expecting something to happen. Nothing does.

There are no murals on the south side, just a warren of industrial buildings that gives onto another street.

You turn right onto that street, and right again. Down a slight hill, through a second peace gate just as intimidating as the first, and just as perfectly maintained.

To your left is a huge concrete wall topped with sheet metal topped with fencing. It’s at least 6 stories tall. Only by crossing the street can you even begin to see what’s on the other side.

You round the corner, and know instantly that you’ve found the Cupar Way Peace Wall.

There are no other pedestrians walking the wall. No tour groups, no information signs – nothing at all to indicate that this is anything other than what it is: a wall built of rage and fear and hatred.

Standing next to the concrete wall, looking up and up and up, you try to comprehend would drive someone to build this wall. And not just a single person, but a whole group of people. A group of people so filled with rage and hate and fear that it came pouring out in these huge walls of concrete and sheet metal and fencing.

You walk slowly along the wall. At first all you can see and feel are the brutality of the wall itself. After a few minutes, there’s space to take in the murals.

The murals are smaller than the ones on the main road. They’re different sizes and shapes, and are much more like spray paint art than picture-perfect postcards.

They’re also covered in graffiti.

The graffiti comes from people of all nations. Most are in English; some are not. Some are calls to action to tear down the wall. Some are statements of solidarity from other minorities in other countries fighting to have their rights recognized by the State.

Many of them are cries for peace – in Northern Ireland, in their home country, in the world. Peace signs are everywhere, and “make love, not war” appears several times.

Some of the messages are so irreverent you can’t help but crack a smile. Others are serious and heartfelt. A few reference the upcoming US presidential race.

You take one picture, then put your camera away. You can’t explain it, but when you think of taking another picture, an almost physical pressure pushes against you. This is an experience that must be felt, absorbed, engaged. To take a picture would be to become the worst sort of voyeur, a way to hide behind the camera instead of absorbing the presence of the hundreds, maybe thousands, of people who have written on this wall.

It’s impossible to read every message, but you try anyway. You go slowly, imagining the people who wrote this message or drew that peace sign with a slight wobble on one side. Were they solo travelers like yourself? Part of a big tourist group? Did they come to Belfast with the express purpose of sharing their story? Or did their experience move them to add their own voice to this mighty wall?

You stand for a few minutes where the road curves and the wall ends. You’ve walked its entire length and back again. A feeling of closure settles over you, mixing with the sound of children playing in a nearby field and cars running in the distance.

Eventually you’ll forget the individual murals, the funny messages, even the poignant ones. You won’t forget how small and vulnerable you feel standing next to several stories of concrete, sheet metal, and fencing. You won’t forget the experience of reading those messages.

And you definitely won’t forget that in the forty-five minutes you’ve been walking the wall, someone has closed and locked the peace gate.

You stare at it, wondering who shut the gate and when. Where did they come from? Are they still nearby? Were they watching as you passed through earlier?

You feel invisible eyes on you from every direction. You’re suddenly aware that you are the only pedestrian, and that the last car you saw was several minutes ago.

Your heart beats a little faster and your steps are a bit quicker until you reach the main road. Here is the comfort and noise of traffic, pedestrians, shops, pubs.

As you head towards your hostel, you think that of all the experiences you’ve had today, the sense of being watched by unknown eyes will stay with you the longest.

Up next: Carrick-a-rede rope bridge, giant’s causeway, and a Game of Thrones tour!

The Peace Talks — you could always delve into the specifics, or go back a few years to the bombings, “Nationalist” fund raising activities (a lot in the USA), etc.

A deeper understanding could take you back to 1921 & earlier with the formation of Northern Ireland.

Even further back is the Plantation Era with the importation of Brit Protestants, etc — Ulster was always known as the “most Gaelic” of the Provinces.

Deep research would take you back to the Viking Era and before, activities between Hibernia & Albion, and Irish Myths & Legends (to fully understand the deep-seated hate)…

I’m familiar with the general ideas and outcomes of both the Plantation era and the formation of Northern Ireland. (I’ve read a few history and historical fiction novels that touch on both areas). I’m not looking to fully understand the hatred – I’m more curious about how the movement to look beyond it and broker peace talks actually came about.

For a perspective on brokering the peace, you might want to fint & read:

“Making Peace”, (Sen) George J. Mitchell

Given that the actual “Peace” is less than a generation old, I’m wondering if the children have the same perspective (anger, hate) that their parents & grandparents do? Values, etc are more inherited than ingrained.

Quite a day in Belfast, with several “journeys” into the recent past. Hate-painted politics & religion along the “Peace Wall”, and inhumanities within the prison. It’s fortunate that prison smells, sounds, etc are gone, but it appears that “hate” still lingers along the wall…

Hate is deep-seated within the Irish, and within the Scots Highlanders (more specifically, A’ Ghàidhealtachd) with whom they share bloodlines, especially in Ulster. From “cattle raids” between hill fort “nobles” 2500+ years ago which have blown into myths & legends, to clan battles and modern-day clashes.

“Interesting” is an inadequate word for people who live their daily lives like any other, but have an innate potential for internal hatred, a hatred that journeyed to the shores of the U.S.A. (post-famine immigration, early history of those immigrants)…

I haven’t been to the Scottish Highlands, though I have no doubt you’re right. The thread of violence that runs through Irish society is something I first picked up on when I house-sat in Dublin over Christmas a couple of years ago. There’s nothing tangible to put my finger on (not like the Peace Walls) but you can feel it if you pay attention long enough.

It’s not the sort of society I’d choose to live in, I think. But having done something unconventional with the last couple years of my life, I understand how difficult it is to go against one’s social and cultural upbringing. For the first time, I’m curious to learn more about the peace talks in Northern Ireland in the 1990s.